A

government-arranged trip to Maungdaw District enabled journalists to learn of

the concerns and needs of some of its 800,000 residents, most of them Muslims.

By NYAN HLAING LYNN

| FRONTIER

GREEN FIELDS, grey mountain

ranges, streams, mangroves, villages sheltered by trees of all sizes, and

occasional glimpses of the Naf River made the travellers on the bus forget

about the bumpy road. They are common scenes in Rakhine State’s Maungdaw

District, which shares a 236-kilometre (147-mile) border with Bangladesh.

But the region’s

natural beauty masks the fear and deprivation that stalk many of the 905

villages in the district, which is home to 700,000 Muslims and 100,000 Rakhine

Buddhists.

Violence scarred

this area six months earlier when Muslim militants launched deadly attacks on

border police posts and the Tatmadaw responded with a massive clearance

operation that generated allegations of murder, rape and the torching of

villages.

Frontier was among

18 journalists, Myanmar and foreign, who travelled to Maungdaw Township and

neighbouring Buthidaung Township on a government-arranged trip from March 29 to

31. We visited 16 villages and four camps for those displaced by communal

violence. Their residents told us of their fears, needs and dreams.

Frontier has decided

not to identify them by name because of recent reprisal attacks against those

who have spoken to the media.

Among them was a

40-year-old Rakhine housewife in Aung Mingala village who said the violence and

its tense aftermath had badly affected livelihoods.

“Now it is worse

than before, when you could go out and work to support yourself and your

family. Now I’m afraid when I hear bad news, especially about the violence,”

she said.

Of the 16 villages

visited by the media team, Aung Mingala was one of two inhabited by ethnic

Rakhine. The other, Pha Wut Chaung, is bigger than Aung Mingala and its

residents seemed to be less anxious. Pha Wut Chaung is a model village – known

as a Na Ta La village – and was established 23 years ago.

A group of Muslim

men building a road in Pha Wut Chaung said they were well and felt safe, as did

a Muslim boy of about 14 with a bicycle who was selling sweets. He could speak

a little Myanmar because he had attended school until second grade.

With the help of the

boy and an interpreter, we learned that the men were from nearby Muslim

villages. They were working as road-builders because they had not been able to

fish or chop wood or bamboo in the nearby forests since the October 9 attacks.

A 55-year-old

Rakhine resident of Pha Wut Chaung said there was no problem living together

with Muslims. However, a 63-year-old former village administrator who has lived

in Pha Wut Chaung since it was founded said he was still in fear of being

attacked in the village and while travelling on the area’s roads.

The

citizenship challenge

The 14 Muslim

villages we visited were all very poor and the atmosphere was not as calm as in

the Rakhine villages.

The Muslim villagers

said they resented not being recognised as citizens of Myanmar, and similar

feelings were expressed by residents of Thepkepyin, Dapaing and Bawdupha 1 and

2, the four IDP camps nearest to the state capital, Sittwe.

All of the Muslims

we interviewed were deeply distrustful of the government plan which requires

them to surrender any identify documents they may have so they can be issued

with National Verification Cards. The NVCs do not guarantee citizenship, but

qualify holders to apply for citizenship through a formal process at a later

date.

Their main reason

for not wanting to be issued with NVCs was the fear they would be labelled

“Bengalis”, the term used by the government and most Myanmar for those who

identify as Rohingya. This is despite the blue-coloured NVCs being different to

previous identity cards because they do not list the holder’s ethnic or

religious affiliation.

Residents of the

Muslim villages insisted on being recognised only as Rohingya, but those in the

four IDP camps said they would accept being described as “Rakhine-Muslim”.

However, people on

the street in Sittwe reject the “Rakhine-Muslim” label.

U Maung San, 59, a

security guard at a hotel in the state capital, said there was no Rakhine group

that was Muslim, although he was apparently unaware of the Kaman, the Rakhine

Muslims recognised as one of the country’s 135 ethnic groups.

Government officials

take a similar line. Border Guard Police Force commander Police Brigadier Thura

San Lwin said that since the time of the former government the country had been

clear there was no group in Myanmar known as the Rohingya.

However, this would

not preclude stateless Muslims in Rakhine State from attaining citizenship, he

added.

If a person’s

grandparents and parents hold a National Registration Card – the forerunner of

the pink-coloured Citizenship Scrutiny Card now in use – then “he or she will

be given a citizenship card immediately after getting an NVC”, San Lwin told

the media group on March 31.

Even if they no

longer have the cards, they can still attain citizenship through the

scrutinisation process, he said.

“Even if their

grandparents don’t have an NRC, if one of the person’s siblings does have one

they will be given citizenship. If there is any evidence that their

grandparents have lived here, they will also be given citizenship,” San Lwin

said.

Despite these

promises, uptake has been very slow. U Than Shwe, Immigration Department

officer for Maungdaw District, said that of its 700,000 Muslims, only 5,000 had

accepted NVC cards.

The border guard

police chief said Muslims who accept NVCs were in fear of being killed by those

within their community who oppose the verification scheme.

“Anyone who accepts

an NVC is threatened and some flee their villages in fear for their lives,” San

Lwin said, adding that the situation was controlled by Muslim community leaders.

“If the leader of a

village permits them to accept NVCs, they will all accept them. Some are

getting them secretly now,” he said.

“The situation on

the ground is such that if you want to receive an NVC, you have to do it

secretly.”

Because residents don’t

hold NVCs, they face difficulties in travelling, working and operating

businesses – including fishing, one of the main income-earners in the area.

The authorities have

denied this is a problem, saying that residents could apply to local officials

for permission to travel. But it was clear when Frontier visited Aleh Than Kyaw

village that the lack of identity cards was having a major impact.

There, more than 100

boats were docked on the riverbank and more than 1,000 workers were unemployed.

“They haven’t applied for an NVC. I can’t run my boats because I have no

workers. I lost about K200 million over the past six months,” said U Than Htay,

an ethnic Rakhine businessman who owns more than 10 boats.

Sithu Aung Myint, a

journalist who has written extensively on Rakhine State and joined the media

trip, said resolving the citizenship issue was fundamental for alleviating the

crisis in Rakhine State.

“They don’t come and

apply for NVCs because [of the rules that have] been imposed. On the other

hand, authorities can only let them do business if they have NVCs. So this is a

big crisis,” he said.

Although the NVCs do

not mention ethnicity or religion, Muslim communities are worried that if they

are approved for citizenship, their new identity card will identify them as

Bengali. Some also object to having to undergo citizenship verification given

that, they say, they were previously recognised as full citizens.

The government says

it is meeting residents in order to build support for its initiatives but this

was not evident when Frontier visited. Most Muslim residents have no access to

newspapers in any language, and few listen to the recently launched radio

station, Mayu FM, which broadcasts in their language.

Instead, they get

their information through Facebook and Viber using SIM cards from Bangladesh,

although they are reluctant to discuss this because it is illegal to use

foreign SIM cards.

A climate

of fear

According to

information released by the government, violence within the Muslim community

claimed 23 lives between October 9 and April 3, with another 10 people missing.

Most of the victims were stabbed by men wearing masks, though two were shot,

the government said.

According to a

recent Reuters report, the killings of Muslims working with the government

began after the security forces embarked on mass arrests of suspected militants

in November. Between October 9 and December 12, the security operation resulted

in the arrest of 524 people on a range of charges, according to official figures.

Despite the massive

security operation after the October attacks, Police Sergeant Tun Naing from

the Border Guard Police post at South Bazaar said militant training camps were

expanding from the Maungdaw area into Buthidaung Township. One of these alleged

training camps was discovered in a gully near Tin May village, in Buthidaung’s

Nga Yan Chaung village tract, on March 1, he said. Seventeen people were

arrested at the camp.

Journalists were

able to meet two relatives of those arrested. They insisted that their

relatives were innocent and that the training was “just a rumour”.

During the visit to

Tin May on March 29, the village in-charge, Hamid Ullah, told journalists he

feared for his safety because he had provided Maungdaw District administrators

with information about militant training camps in the area. He complained of

not being provided any security, despite receiving threats.

Two days later, he

was dead. A group of masked men broke into his home around 1:15am on April 1

and slit his throat while he was sleeping, according to a government statement.

He was the second

man killed after speaking to the media. The first, from Ngakhuya village,

disappeared a day after a conversation with journalists during a press trip in

December. He was found dead one day later.

When Frontier

questioned Muslims residents about these killings, they refused to discuss

them.

It was clear that

they live in fear of both the government as well as the insurgents. But they

were more willing to discuss allegations of abuses by the military since the

clearance operations were launched in October.

In every village

residents told Frontier that buildings had been torched and women raped –

accusations that have been widely documented, including by international media

and the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights in a damning report

released in February. However, except in one case – the allegations of rape in

Kyar Gaung Taung – they could not provide evidence or clearly specify what had

happened.

In March, a senior

Tatmadaw official rejected abuse allegations reported in the media. When the

military investigated the claims, residents had responded that they were

unaware of any abuses taking place, said General Mya Tun Oo, chief of the

General Staff.

“I want to say that

I am very sad because of these kind of reckless accusations and neglect of the

good things that the government and the military have done for them,” he said.

The military has

formed an investigation team to examine the allegations and the Ministry of

Home Affairs has initiated its own probe. According to the recent Reuters report,

the military team had interviewed the commander in the area, Major-General

Maung Maung Soe, and several of his senior staff, as part of the investigation.

The authorities

insist that they are investigating every formal complaint that has been made. Despite

the widespread allegations of abuses, only 18 complaints have been submitted,

according to the No 1 Border Guard Police Command Centre, including 13 cases of

manslaughter or murder, three of rape and two of robbery.

Of these, the

military is accused in the three rape cases and one of killing by gunshot.

San Lwin said

autopsy results had indicated that 11 of the death cases occurred at least a

year ago.

Two remain open,

including one involving a man and three women whose remains were found in Kyet

Yoe Byin village. Bullet wounds were found on three bodies and the autopsy

indicated they died around six months ago.

In the other case, a

woman in Zin Paing Nyar village said her husband was shot dead on November 4,

2016.

The two robberies

are being investigated, San Lwin said. One rape complaint has been dismissed

after a medical examination, while in another the complaint has been accepted

and an investigation is underway. In the third, the authorities are waiting for

the results of the examination before deciding whether to proceed.

During the media

trip, three women from Kyar Gaung Taung village told reporters that they had

been raped by soldiers three months earlier, and police subsequently opened an

investigation. “The security forces put us together in groups of three or five

and then we were taken to a house where there were no people and four or five

people raped us,” said one of the victims, a 16-year-old girl.

Similar allegations

have previously been made by women in the villages of Kyet Yoe Byin and Pyaung

Pike. However, when officials went to meet the accusers, one had fled and the

other said, via a village administrator, that she didn’t want open a case.

The low number of

formal complaints reflects a lack of confidence in the police to properly

investigate the allegations.

Residents said that

although the incidents really occurred, they were afraid to submit complaints

to police because of language problems. They believed that because of this the

police might not investigate or the court might misunderstand the allegations,

they said.

“We dare not open

the case because transportation [to the police station] is difficult and we are

afraid that the police might not record what we said accurately,” said a male

resident of Kyar Gaung Taung, when asked by Frontier why they had not taken

their complaints up with police.

There is also a fear

of the potential consequences should the complaint be dismissed.

San Lwin said that

police had taken action against a complainant in one case because they did not

have evidence to support their complaint. He refused to say what action had

been taken.

In another incident,

in which residents of Kyar Gaung Taung said a house had been torched and a body

buried, the complainants were unable to say exactly where the incident

occurred. San Lwin said the authorities have asked for legal advice on whether

they should face criminal action.

He said that for the

most part police did not take action when accusations could not be

substantiated.

“Although some

complaints are apparently untrue, we have ignored them because of the current

situation,” San Lwin said.

Meanwhile, he said

that about 20 soldiers and police who have failed to abide either civilian or

military rules have faced disciplinary action. Again, San Lwin declined to give

specifics, saying only that action had been taken under civilian and military

laws.

“They might have

committed crimes while on duty. But we can’t say exactly that they have

committed crimes. If they have, then we will take action against them in accord

with the law.”

The

reporting challenge

The language barrier

also poses significant difficulties for journalists working in northern Rakhine

State. Only a few people in each village could speak Myanmar. Interviews with

these people usually took place in front of large groups of residents.

Sometimes when

individuals were answering, a person in the crowd would speak to them in their

own language. We worried that the interviewee was being silenced or being told

to change their account, but had no way of knowing what was being said.

Another case that

made journalists uneasy was in Tin May village. When a group of journalists

asked the relatives of those detained for allegedly attending militant training

whether they had been able to meet them while they were in prison, they

answered that they had seen them a few days ago.

But when another

journalist asked them the same question later, somebody in the group said

something to them, and then the answer changed; they said they hadn’t yet seen

their relatives.

Journalists were

also concerned that the interpreters might have not properly relayed what

residents had said.

Daw Ei Ei Tin, a

journalist from Fuji TV, said that given most people couldn’t understand

Myanmar language she was very surprised to be given a letter of several pages

in English outlining accusations of “genocide” against the Tatmadaw.

The letter had

originally been addressed to UN special rapporteur on human rights, Ms Yanghee

Lee, but her name had been erased. It purported to be from residents of Pwint

Phyu Chaung village tract, and said that in their village 29 people had been

shot and killed by the military and their bodies burned.

The letter also

accused security forces of raping 11 women and burning 379 of 423 homes in the

village. It urged an investigation and the creation of a “durable solution” for

the Rohingya people.

Another indication

that some north Rakhine residents were in close contact with the outside world

despite the poor local telecommunications infrastructure came on March 30.

In Kyar Gaung Taung,

a woman told us that she had been raped. Before we had returned to Maungdaw,

residents had already informed the Myanmar service of Washington-based VOA that

she had been detained by police.

The authorities

refused to provide any updates on the case until the morning of April 6, when

they revealed that they had taken her to the police station together with

village officials in order to accept a formal complaint from her.

All the reporters on

the press trip said that they were able to gather news independently, except

for the first day, when some government staff recorded the personal information

of the interviewees. We then negotiated with the authorities and they agreed

not to be present during interviews for the rest of the trip – an important

step for encouraging residents to speak openly.

But the tragic

killing of Hamid Ullah – who had spoken to journalists on the first day of the

trip, when the authorities were present – highlighted the need for the

government to provide better security for those who agree to speak out.

If the security of

residents cannot be ensured, it will be difficult for journalists to gain an

accurate picture when they visit the region, said Ko Aung Thura, a reporter

with VOA (Myanmar).

But arguably the

biggest challenge was simply sorting fact from fiction, said Ma May Kha, a

reporter from VOA’s Myanmar service.

“It’s difficult to

say,” she said, “whether the news we got was true.”

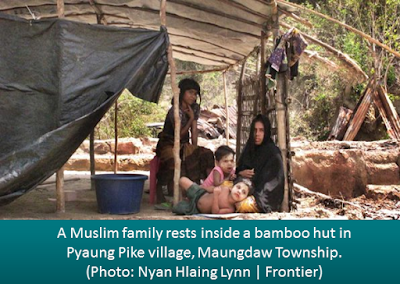

TOP PHOTO: A Muslim

family rests inside a bamboo hut in Pyaung Pike village, Maungdaw Township.

(Photo: Nyan Hlaing Lynn | Frontier)