Amid Rohingya crisis, Nobel laureate

treasures strong family link to the military

BANGKOK -- Few people have enjoyed more uncritical press

coverage or been the subject of so many fawning biographies as Aung San Suu

Kyi, Myanmar's de facto leader and the 1991 Nobel Peace laureate.

But many believe Suu Kyi's aura is gone, and that she has

feet of clay. Both aloof and imperious, her infrequent encounters with the

press have become "lectures and platitudes," according to one Burmese

editor. Of late, Myanmar's 73-year-old state counselor has made one tone-deaf

statement after another to foreigners.

Addressing a half-filled gathering at the World Economic

Forum on ASEAN in Hanoi last week, she dashed hopes for a presidential pardon

for two young Reuters journalists. The two have been sentenced to seven years

in prison for breaking a 1923 British colonial law designed to enforce the

presence of a foreign occupying power. The journalists had been investigating

atrocities committed last year against the Rohingya Muslim minority in the

northwestern state of Rakhine. United Nations officials have described the

killings as textbook ethnic cleansing.

"I wonder whether very many people have actually

read the summary of the judgment, which had nothing to do with freedom of

expression at all -- it had to do with an Official Secrets Act," Suu Kyi

said, responding to a question about the journalists' conviction. "If we

believe in the rule of law, they have every right to appeal the judgment and to

point out why the judgment was wrong."

Suu Kyi's words met a ferocious response, particularly in

light of strong evidence of entrapment by the arresting police officers.

"This is a disgraceful attempt by Aung San Suu Kyi to defend the

indefensible," said Amnesty International's Minar Pimple. "From start

to finish, the case was nothing more than a brazen attack on freedom of

expression and independent journalism in Myanmar."

Others were equally vocal. "She fails to understand

that real 'rule of law' means respect for evidence presented in court, actions

brought based on clearly defined and proportionate laws, and independence of

the judiciary," said Phil Robertson, U.S.-based Human Rights Watch's

deputy director for Asia.

Nikki Haley, the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations,

condemned Suu Kyi's remarks on Twitter. "First, in denial about the abuse

the Burmese military placed on the Rohingya, now justifying the imprisonment of

the two Reuters reporters who reported on the ethnic cleansing.

Unbelievable," she wrote.

"Many observers saw this trial as a test of freedom

of the media, democracy and the rule of law in the country," Federica

Mogherini, who leads the European Union's foreign policy, told the European

parliament. "It is pretty clear that the test was failed."

Suu Kyi's comments in Hanoi rekindled the severe

criticism of her last month in Singapore when she described three generals in

her cabinet as "rather sweet." The three include Lt. Gen. Kyaw Swe,

the minister of home affairs. His ministry controls the police, and is

therefore directly linked to the Reuters case.

For decades, Myanmar has been criticized for failure to

establish the rule of law. A hodgepodge of pre- and post-independence laws has

been used to suppress opposition and criticism. Myanmar's juntas always claimed

to be doing things "according to the law."

"To argue that the letter of the law was followed is

to willfully ignore all of these glaringly obvious shortcomings," Pimple

said after Suu Kyi's Hanoi comments. "It's also eerily similar to the line

taken by the military generals when Aung San Suu Kyi herself was locked

up."

Suu Kyi built her reputation after a mass pro-democracy

uprising in 1988. With bows to Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., she

called for peaceful resistance, political reform, national reconciliation and

respect for human rights. As a pro-democracy icon, she was always stronger on

Buddhist and humanitarian principles than clear policies.

During about 15 years of off-and-on house arrest by the

military in her lakeside villa in Yangon, the few correspondents occasionally

able to reach her tended to place her on a pedestal, overlooking her political

and economic inexperience. She was hailed by U.S. Secretary of State Hillary

Clinton and President Barack Obama, among many others, and showered with awards

and accolades. A growing number of these have been withdrawn following the

exodus to Bangladesh of over 700,000 terrified Rohingya, but not the Nobel.

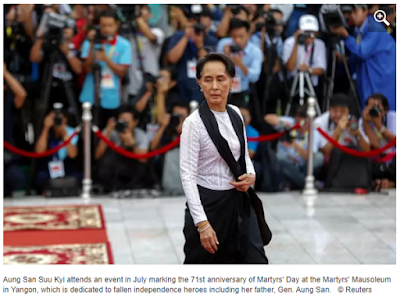

Despite the military's evident enmity toward her, Suu Kyi

over the years has shown herself to be more than conciliatory. She makes

frequent rose-tinted allusions to her father, Gen. Aung San, the

pre-independence hero and founder of the Burma Independence Army in 1941 backed

by Japan but her father who was assassinated in 1947 by a jealous political

rival, played very little role in the development of the military.

The armed forces were developed by Aung San's nemesis,

Gen. Ne Win, whose coup in 1962 set the nation on a regressive, xenophobic and

economically disastrous path. The nation's modern history has been further

blighted by more than a dozen ethnic insurgencies.

Even in the darkest times over the past three decades,

Suu Kyi often referred to her military oppressors somewhat deferentially as

"the authorities." She has been open about her weakness for men in

khaki. "I was taught that my father was the founder of the army, and that

all soldiers were his sons, and that therefore they were part of his

family," she told Desert Island Discs, a popular BBC radio program, in

2012.

"I am fond of the army," she said. "People

don't like me saying that. There are many people who have criticized me for

being a poster girl for the army -- very flattering to be seen as a poster girl

for anything at this time of life."

Asked about military atrocities that include recruiting

child soldiers, planting land mines as well as rape and murder, Suu Kyi said:

"I don't like what they've done at all. But if you love somebody, I think

you love her or him despite, not because of, and you always look forward to a

time when they will be able to redeem themselves."

Suu Kyi also clearly signaled her position on the

Rohingya issue in 2012 following an earlier round of strife.

"I didn't come into politics to be popular,"

she said. "If I were to take sides in the situation in the Rakhine ... it

would create more animosity between the two communities. Violence has been

committed on both sides. People who are afraid of being burned in their beds

are not going to talk to one another and try and find a way out of the

situation. I have been saying all along what we need is security and the rule

of law."

The BBC's Fergal Keane, a longtime admirer of Suu Kyi who

had reported ethnic cleansing in Rwanda and the Balkans, challenged Suu Kyi on

developments in Rakhine State in April 2017, a few months before the main

Rohingya exodus. "Do you ever worry that you will be remembered as the

champion of human rights, the Nobel Laureate, who failed to stand up to ethnic

cleansing in her own country?" he asked.

"No, because I don't think there's ethnic cleansing

going on. I think ethnic cleansing is too strong an expression for what's

happening," said Suu Kyi.

"It's what I think I saw there, I have to say,"

said Keane.

"Fergal, I think there's a lot of hostility

there," said Suu Kyi.

With so much opprobrium now being heaped upon her, and

having lost so much international support, at least Suu Kyi cannot be faulted

for inconsistency. The rule of law in Myanmar remains as elusive as ever,

however.

Source: