Steve Sandford VOA

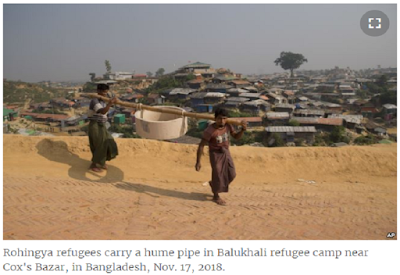

More than 750,000 Rohingya Muslim refugees

who fled military attacks in Myanmar remain in Bangladesh camps as future

repatriation and resettlement plans remain unclear.

VOA Video: https://www.voanews.com/a/4711900.html

Across the sprawling camps in Cox’s Bazar,

close to a million Rohingya Muslim refugees remain in limbo — without a clear

future.

Voluntary repatriation plans last month were

postponed amid security concerns about ongoing abuses and a lack of

international monitoring.

The Myanmar government has allowed tightly

controlled trips for international media in recent months, but access to areas

where alleged atrocities were carried out has been denied.

In Bangladesh, published footage of a

resettlement compound on the remote Bhasan Char Island was also being viewed

with concern.

“The UNHCR has not been let on the island to

do a risk assessment of the flood conditions but many say the island is prone

to flooding and dangerous that means that thousands of Rohingya refugees could

potentially be on a flood prone island and that’s a very dangerous situation,”

said John Quinley III, a human rights worker for Fortify Rights.

The concrete compound with barred windows

awaits an estimated 100,000 refugees who will be transferred from Cox’s Bazar

onto the remote silt island, built up by Chinese construction crews and the

Bangladesh navy.

With the Bangladesh election set for December

30, any move to repatriate people or relocate refugees to the remote island

will be postponed until 2019.

Education prospects

The long-term impact on the Rohingya

population are yet to be felt, but analysts say the prolonged denial of

education for the school-aged children will be damaging.

“Rohingya in Rakhine, that Fortify Rights has

spoken to say that the situation on the ground right now is an apartheid state.

They have no freedom of movement, no formal access to education; Rohingya

students in Sittwe that want to go to Sittwe university cannot go there,”

Quinley added.

The U.N. Children’s Fund (UNICEF) presents a

bleak assessment of the future for children on either side of the border,

speaking of a lost generation of children and youth.

UNICEF said it was widening education

programs in the Bangladesh camps, currently for children up to the age of 14,

to try to meet the needs of older children. A UNICEF spokesman told VOA that

"programming for youth including education at post primary level remains a

clear gap which urgently needs to be addressed by increasing both the range of

services and access opportunities for youth. The lack of education and economic

opportunities exposes this population to multiple risks including drug abuse,

and gender-based violence and extremist views."

UNICEF points out that even more basic than

education needs are the health challenges faced by the Rohingya: "Despite

nine massive vaccination campaigns since October 2017 until May 2018

(delivering over 4.2 million doses of vaccines), routine immunization since

June 2018 remains a challenge. The children are still vulnerable and at risk of

a potential disease outbreak. Continued health support is critical to assist

the refugees and especially children to survive in the crowded refugee camps."

Land issues

And while the life in the camps can be hard,

it is not clear if the Rohingya will ever have anywhere to go back to in

Myanmar.

Authorities in Myanmar say land that has been

burned becomes government managed property, casting into doubt the ownership of

more than 200 Rohingya villages that were burned to the ground in the past year

and a half.

Rohingya lawyer Kyaw Hla Aung said official

records can prove rightful ownership, provided they are requested.

The 78-year-old activist just won the Aurora

Prize for Awakening Humanity - a global humanitarian award - for his dedication

to fighting for equality, education and human rights for the Rohingya people in

Myanmar, in the face of persecution, harassment and oppression.

With a background as a law clerk for more

than two decades in Rakhine state, Kyaw Hla Aung is adamant that land ownership

should be easily proven for returning Rohingya citizens.

“They have all the documents, all the records

in the land record office in the home ministry,” he said. “The international

community should ask the government to show all these records.”

“They are not only confiscating the land in

Rakhine state but also in Shan state, Kachin state and in the midst of Burma in

Karenni state as well,” he added.

Justice concerns

Accountability and justice are other key

factors in delaying any form of voluntary return.

“Rohingya that we have spoken to say they

won't go back to Rakhine state until there’s restored citizenship rights and

accountability for the atrocities that have occurred,” said Quinley.

Analysts see the ongoing restrictions and

attacks as a pattern indicating deliberate actions to eliminate a group.

Officials in Myanmar have consistently denied

allegations of abuse and repression against the Rohingya, saying its military

has conducted legitimate operations against terrorists.

Earlier this month, (Dec. 13) the U.S. House

of Representatives passed H. Res. 1091, declaring the crimes carried out during

the Myanmar military clearance operation as genocide.

“The most recent wave of persecution began in

August of 2017, when Burmese security forces and civilian mobs began a horrific

wave of attacks,” said Chairman Ed Royce, on the house floor.

“Mass murder, rape and destruction of

villages throughout Rakhine State have been documented.”

Activists say the ongoing persecution of the

Rohingya Muslims has all the earmarks of a genocide, including lack of access

to education, an action by the state government, that was increased since the

2012 communal violence in Rakhine state.

“The government is making us illiterate so

that they can allege that these people are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh

because they don’t know anything about the world,” explained Kyaw Hla Aung.

Commission report

At a news conference this month, Rosario

Manalo, chair of Myanmar’s Independent Commission of Enquiry, stated that the

commission had found “no evidence” to support allegations of human rights

abuses in the four months since it officially opened its investigation.

“We will clarify how we collected the

evidence later. But for the time being, allegations are still allegations.

There is no conclusive evidence,” the former deputy foreign minister of the

Philippines added, during the press conference.

The commission started their investigation

Aug. 15, and is to submit its findings to the Myanmar president’s office by

August 2019.

Rights groups are condemning investigation

commissions that have been set up by the Myanmar government.

“The Myanmar commission’s dismissal of the

extensive documentation of gross human rights abuses against the Rohingya makes

abundantly clear that it is not serious about seeking justice,” said Brad

Adams, Asia director at Human Rights Watch. “The U.N. Security Council should

stop giving credence to this commission and refer the situation in Myanmar to

the International Criminal Court (ICC).”

The ICC ruled in September that it has

jurisdiction over alleged deportations of Rohingya people from Myanmar to

Bangladesh as a possible crime against humanity.