MAUNGDAW, Myanmar — We waded through floodwaters, past

soldiers hefting rifles, and climbed into a prefabricated hut.

Inside, a row of men sat huddled against the wall as

armed police and immigration officers stood over them. They were, we had been

given the impression, among the 700,000 Rohingya Muslims who had fled northern

Rakhine State in Myanmar for Bangladesh last year in an exodus that the United

States and other countries condemned as ethnic cleansing.

Now, dozens had been repatriated, officials said, thanks

to the good will of the Myanmar government, which wanted to show off its

commitment to welcoming back the Rohingya and the rows of barracks it had

prepared for the returnees.

But like nearly every interaction on a recent

government-led trip for journalists to the epicenter of the crisis, cracks

appeared in the official story line.

The men at one of the country’s three repatriation

centers shook their heads when asked if they had peacefully come back to

Myanmar from Bangladesh.

They said they had not been repatriated at all. In fact,

they said, they had never even left this waterlogged stretch of marsh and

mountain in Myanmar, and had been swept up in the government’s broad repression

of the Rohingya minority.

One day, last year, three of the men said, soldiers had

arrested them in their village in northern Rakhine State. Five and a half

months later, they were released and charged with illegal immigration.

“They accused us of coming from Bangladesh, but we have

never been to Bangladesh,” Abdus Salim said. “Rakhine is our home.”

U Win Khine, the lead immigration officer, looked

apologetic. Maybe they were liars, he said. He refused to call the men

Rohingya, referring to them as Bengali to imply they belonged in neighboring

Bangladesh.

“Bengalis are not from our country because they have

different blood, skin color and language from us,” Mr. Win Khine said. “We have

no Rohingya here.”

Outside of Myanmar, the tragedy of the Rohingya is clear.

Over the decades, the Muslim minority has been stripped of its rights — to

attend college, to access medical care, to move freely — by a

Buddhist-chauvinist, army-dominated government. Most have no citizenship.

When Rohingya insurgents attacked police posts and an

army encampment last August, killing a dozen security personnel, a paroxysm of

violence against Rohingya civilians followed within hours: mass executions,

rapes and village burnings by security forces that United Nations officials

have suggested could constitute genocide. Rakhine Buddhist mobs are abetted in

the bloodletting.

But on this rare trip to northern Rakhine, under the

watchful eye of armed guards, the official narrative diverged from the

internationally accepted reality. The Rohingya had burned their own residences,

we were told by officials and civilians alike. They were terrorists — and if

they were not terrorists, they were women and children manipulated by shadowy

groups in Bangladesh and elsewhere in the Islamic world.

Yet even as we were shepherded through the muddy, still

charred countryside of Rathedaung and Maungdaw, two townships in northern

Rakhine, the discussions grew sticky with contradictions.

We stopped in a village once populated by Rakhine

Buddhists, Rohingya Muslims and the Mro, a formerly jungle-dwelling ethnic

minority. Eight Mro were killed last August by Rohingya insurgents, the Myanmar

authorities have said. Why hadn’t the international media covered these

murders, local officials on our tour asked? But they didn’t address the thousands

of Rohingya who human rights groups say were killed last year.

Like everywhere else we went, officials in the village

insisted that the Rohingya here had torched their own houses in order to garner

global sympathy.

But at one point we spoke freely with local residents,

and a girl, who would be in danger if her name were revealed, said she missed a

Muslim friend who had lived a few houses down. “The Rakhine burned their houses

down,” she said, referring to civilians from the Buddhist ethnic group that

gives Rakhine State its name. “My friend is gone forever.”

A man corrected her quickly. “You’re supposed to say the

reverse,” he admonished. “You should say they burned their own houses down.”

Outside, another child, playing soccer barefoot in the

rain, was more emphatic.

“I saw it with my own eyes, how the Rakhine burned down

all the Muslim houses,” he said, detailing how a car belonging to a Rohingya

family was lit on fire because the looters didn’t know how to drive.

“Who would burn down their own houses?” the boy added.

“That’s stupid.”

A new school and Buddhist pagoda had been built on what

was once the village’s Muslim quarter. The remaining residents have been gifted

new homes by the government, rows of prefabricated houses that looked

incongruous in one of the poorest places in Asia.

In the town of Maungdaw, U Kyaw Win Htet, the assistant

director of the Maungdaw District General Administration Department, gave a

briefing on the area’s changing demographics. A year ago, Maungdaw District had

a population of 800,000. Now, there were 416,000 people. Before, the township

was 90 percent Muslim. Now it was barely half.

Why did the Muslims leave? Mr. Kyaw Win Htet, a Buddhist,

said he wasn’t sure. “I think they didn’t want to live here anymore,” he said.

“But the reason why, only they themselves know.”

Did the local government have death tolls from last

year’s violence, broken down by ethnicity? Mr. Kyaw Win Htet said he did not

know. Had he ever visited any of the hundreds of burned Rohingya villages? No,

he had not. Did he know of any Muslim employees of his government department,

given that nearly most of the district’s population had been Rohingya? No, he

did not.

Later, Mr. Kyaw Win Htet admitted that the “Bengali

issue” was not his bailiwick. His expertise was flood control. He had been

assigned to talk to us only because his boss was away.

Earlier this week, the Myanmar government formed yet

another commission to investigate what exactly had happened in northern

Rakhine. Half a dozen such committees have been convened so far; none has

determined anything substantive.

Meanwhile, the country’s leadership continues to deny there

was any state-sponsored campaign to remove the Rohingya from Myanmar.

At one swollen river crossing, a few Rohingya ventured

through the murky water. We had gotten out of the car because it wasn’t clear

whether the vehicle could manage the current, and an elderly woman, Suma Bibi,

and her husband splashed by. I wanted to talk to her so we ducked under the

roof of a border guard hut to escape the rain. She was shaking.

“I am afraid,” she whispered, jutting her chin at the

armed policeman standing behind me. “I don’t want to be close to people like

that.”

Ms. Bibi said she had tried unsuccessfully to escape to

Bangladesh when her village was destroyed by fire.

“I want to leave,” she said. “But I cannot.”

We had with us an armed guard, Cpl. Ko Hla Phyu, who

wasn’t pleased when we talked to Muslims or showed too much interest in the

scorched wrecks of mosques. The corporal said he knew all about the

“terrorists,” who had created havoc in northern Rakhine.

When the photographer with us, Adam Dean, defied his

instructions and jumped out of the car to take pictures of a charred village,

he remarked that if Adam’s head wasn’t bulletproof, it would be advisable to

return to the car.

“I will lay down my life to make sure the terrorists

don’t get my gun,” he said, cradling his battle rifle.

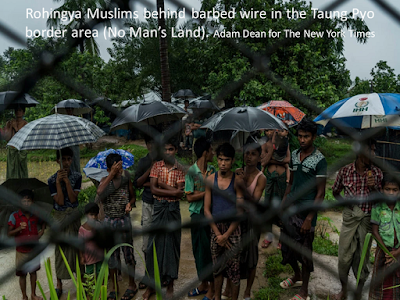

The final day of our government tour, we stopped at the

Taung Pyo border between Myanmar and Bangladesh, where thousands of Rohingya

have been caught behind barbed wire in a kind of buffer zone between the two

countries. The Myanmar government claims Muslim militants operate from this

narrow strip of territory, a charge these displaced Rohingya deny.

On earlier occasions, from the Bangladesh side, I had

talked with Dil Mohammed, the leader of this marooned community. Mr. Mohammed

had gone to the University of Yangon, Myanmar’s finest. He once had a nice

house. Now he was stateless, homeless and soaked by the monsoons and the

occasional surge of sewage.

But he laughed when he saw me peering through the fence

from Myanmar.

“Before, you were on that side,” Mr. Mohammed said in his

courtly English, pointing to Bangladesh. “Now you are on this side.”

“But I am still here in the same place,” he added. “Do

you think that will ever change?”